- Home

- Matthew M Bartlett

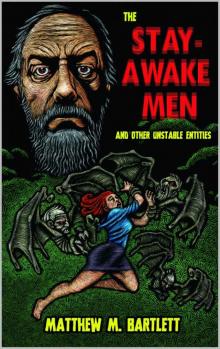

The Stay-Awake Men & Other Unstable Entities Page 5

The Stay-Awake Men & Other Unstable Entities Read online

Page 5

Daniel is again left alone with his thoughts. They are not welcome companions. He considers his belly, now hanging over his belt-line. His belt digs into his flesh when he sits, carving painful welts into his waist. His own heartbeat nags him about his mortality. He is aware of it more and more as he ages, especially in the silences when Mary’s gone out or sits sequestered in her room. It thumps out the years like a kitchen timer. Like anything else, it will stop, ring the harsh and jarring bell of finality. It could do so at any moment, as his father’s had; the old man had simply crumpled to the kitchen floor while scrambling eggs, the spatula gripped in his white-knuckled hand.

Further, Mary has been complaining that she can hear his snoring from her room. He probably has sleep apnea. Stops breathing who knows how many times a night. And he speculates at what tiny cancers might even now be multiplying somewhere in the murky purple depths of his body. He turns over in his tired mind every fatal scenario he can conjure. Death flies among his thoughts, a black wraith tracing a zig-zag path among moon-drunk birds.

Daniel turns on the television to silence his thoughts. Channel 22 is interviewing a beloved coach about his retirement…and damned if one of the things isn’t perched atop city hall in the background, blurry, but unmistakable; its spindly legs twitching; rheumy, hate-filled eyes surveying the town common. Daniel sits up in the chair, stares. His hands open and close. He wants to shout, to warn the people on the screen. The thing’s talons scrape the brick, red clouds spill down onto the walk below. A couple walking below see the thing, flinch, scurry into traffic, protecting their faces with crossed forearms among the screaming of car brakes and the shouts of horns. Not a word from the reporter as the coach prattles on, oblivious. The thing launches awkwardly from its perch, lurches through the sky and off-screen.

He calls the station’s You Report It Hotline. The phone rings and rings.

The door slams and the cat bolts from Daniel’s lap and runs into the kitchen. Mary rushes in and the hood of her coat is torn, her forehead scraped, dots of blood clotting along a ragged line like points on a graph. Her strawberry blonde curls are matted, mud-caked. Daniel starts to rise and she flutters a dismissive hand in his direction.

-Fucking things. I’m fine. Where’s the disinfectant…I’ve got it.

Off to the bathroom. The sink runs, water splashes. A door closes and music starts up and she’s in her room ignoring everything. She has been stoic, sullen since before this thing began, since the disaster with Keith, about which she refused to give any information at all—an incident, Daniel supposed, or an unresolved argument—that saw her arrive at Daniel’s unannounced with a suitcase full of clothes and unknown depths of unexpressed rage and disappointment. Now he is unwillingly cast in the role of the father who can’t do or say anything right, and all he can do is wait for her to come around. It would feel better, he thinks, to have an ally. It would feel better for her too, he knows it. Until she comes around, the feline will more than suffice for uncomplicated companionship. As though summoned by the thought, the cat saunters back into the room, tail swimming lazily behind her. She jumps to Daniel’s side and sinks into sleep.

That night, something new, something bad. Daniel awakens to voices echoing outside, unintelligible, punctuated with dark chortling and sibilant whispers. He feels for the cat but she is no longer at his side. He rises, crosses the dark room to the window, parts the curtain. The moon is high and bright, the sky cloudless. Stars glint, smug and safe up in the firmament. The emptied houses’ windows hang open, and the voices thrum within, in the dark, empty rooms. He can’t make out individual words, can’t even tell if they’re speaking English. The voices overlap, converge and declaim in unison, then part into separate streams of droning monologues. They don’t stop for breaths. Daniel turns on the fan to block out the sounds with white noise, but still he hears the percussive voices, now strident, now clandestine, now ecstatic. He falls into uneasy sleep as the cat, who has returned to his side, twitches and squeaks out complaints, her tiny teeth clicking.

In the morning Daniel dares step out onto the porch, then down to the lawn. It’s warm for November. The sun glistens off the dewy branches that crowd the quiet street. He hears birdsong, a rare sound now. They sound cautious, staccato chirps and trills and titters. The windows of the other houses are still open, but all is still. He doesn’t even see any of them. He usually sees two or three sleeping at dawn, tucked into the crook of a branch or on a housetop. They clench like wounded spiders, and they shiver and twitch. Their ribs stick out. Their sides heave. One will, on occasion, push out a loud, rattling fart. Daniel once saw one break wind, wake, and, grotesque arms pinwheeling, fall from its perch on a high telephone wire. He laughed—he could not help but laugh—but he stopped laughing when it hit the ground. He has to block his memory now of what happened when it hit the ground.

Beyond the hedge he spots Mary’s shoe on the road and his heart starts to thrum in his chest. The air seems to buzz with menace. Dark droplets on the pavement lead to the shoe, or away from it. Are they blood drops? He backs up, keeping an eye on the space between the hedges. He closes the door and latches it, heads for Mary’s room. The door is open, the bed unmade, the sheets and blankets piled at its foot.

He goes back outside, grabs his cane on the way out. A flimsy weapon, but a weapon nonetheless. The cat yowls as he passes. The shoe is still there, and now he hears something. A whimper. Holding the cane out in front of him in both hands, he advances toward the street. He braces himself, passes between the hedges. He looks at the shoe, kneels, touches a droplet and examines the tip of his finger. Brown liquid has settled into the whorls of his fingertips. He sniffs at it, wincing. Not blood. Motor oil.

Mary’s car is still in its spot. He rises and turns to go back inside.

Three of them stand sentry in front of the front door. They are emaciated. Blue veins as thick as fingers pulse in their sagging wings. The layered, drooping folds under their eyes are black and bruised. One has a skin tag the size of an apple hanging on its cheek, dark red and bleeding at its root. Its weight pulls down the skin under its eye, creating a cradle of red below the pupil in which maggots cavort in a squirming orgy. The things open their mouths, revealing purple-soiled graveyards of disarranged grey teeth, and sing a high, mournful chorus, an alien, synchronized sigh. A barbershop quartet, Daniel thinks. But where is the fourth?

Hot, damp hands grasp the back of his neck and squeeze.

The thing whips him around, dropping him onto his back and pinning him, its wings flapping wildly. Daniel’s cane flies from his hand, landing in the hedge. The thing’s feet dig into his gut below the arch of his rib cage. Its eyes betray fierce anger rimmed around the edges with profound sorrow. It pulls Daniel's face to its own—Daniel deliberately unfocuses his eyes and lets his mouth go slack—and it kisses him gently on the lips, dry and feathery.

It loosens its grip and rolls off of Daniel onto the leaf-strewn walk. Its hands grapple uselessly at the air and it coughs, its body trembling with each concussive hack. Then the trembling quickens, its toes spread and stretch, and it dies, its eyes rolled rightward, staring through Daniel and into unknown abysses. It clenches and shoots a stream of miserable grey diarrhea onto the walk.

Daniel pushes himself into a sitting position, lurches forward, and stands. His legs are weak and shaking. The veins stand out in his arms as he puts his hand to the back of his neck to check for blood. It stings. It stings like a thousand jellyfish. The three things that had been blocking the door have flown up to the eaves, where they weep noisily, shining pendulums of yellow-green mucous swaying from their nostrils.

Daniel retrieves his cane, makes his way up the porch steps, caroms through the front doorway and into the dark living room, falls into his easy chair. He closes his eyes, listens to his own breathing as it calms. At some point the cat jumps onto the arm of the chair, then jumps back down and gallops out of the room hissing. His skin feels as though it’s shrinking, tightening

in increments like a blood pressure cuff. His arms feel week and flabby. He tries to lift one and cannot. His eyes burn and he is unable to attend to them. Am I dying? he wonders. Am I dead?

The answer comes two hours later when the creak of the door awakens him. He lifts the lid of one eye and sees Mary silhouetted in the evening light. She smells of blood, of infected flesh. Oh, Dad, she says, and she comes and kneels next to him. She touches his face with one hand, lifts his wrist with the other. Her hands are as hot as fire.

Oh my god, Dad, she says.

kuklalar

Artemis entered without knocking and rapped his knuckles on the side of the filing cabinet. I was struggling with the wording of an Official Company Statement due to my superiors before the end of the day, so I shook my head no, but he held up three fingers, each meant to represent one minute of my time. I rolled back my chair, stood, and pulled on my jacket. I knew from experience that it would take considerably longer than advertised, and I’d already guessed the topic of the desired conversation: the renovations, now in their third week, smirking workmen and ladders and dust, wires hanging from the drop ceiling like intestinal loops, no word from corporate as to what exactly was being installed. Impeding one’s progress through the corridors were ladders, unruly deadfalls of metal tracks, large metal tool cases, and industrial-size rolls of high-tensile wire that resembled metallic hay bales, materials for the installation of two sets of tracks into the hallway ceilings and the running of wires along them. The noise proved intrusive and distracting: drilling, hammering, sawing, instructions shouted from man to man.

In fact, Artemis did not want to talk about that. We stood with our backs to the wall in the courtyard between the two buildings that comprised the campus, shielded from the rain by a slight overhang. He ran his hands back and forth over his rumpled white hair until his coiffure came undone, forming a storm cloud around his head. He looked like a mad scientist. Shielding his lighter from the wind, he lit a cigarette, and I lit my own off of his. His ruddy hand trembled as he drew the smoke into his lungs. I noted the dry skin at his knuckles, honeycombed with cracks, some of them red with blood. “There's a cabal against me in this place,” he said, smoke billowing out around the words.

“Do you think so?” I said.

“Martina Denton's in on it. And Glen what’s-his-name. Dale Kherr, in Maintenance? What it is is, the people in power don't like me because I lack an internal censor—I got this from my father, who was fired from more jobs than I’ve ever held—I tell them the truth. The unadorned truth.” He pointed a cigarette-yellowed finger at me and jabbed it into the air a few times. “And do I like being in this situation? Do I enjoy being on the bubble?”

“Of course not.”

He grinned, revealing teeth stained from tobacco smoke and profusely chipped at the edges. “Of course not. It's just that I'm not...what's the word?”

“Constitutionally.”

“Not constitutionally able to prevent myself doing so.” He paused, looked skyward. “I think I was looking for 'congenitally.' At any rate, I want you to watch my back, will you? If you hear anything, anything they might have on me, you’ll let me know, won’t you, buddy? Can I give you that assignment? Will you be my eyes and ears, if I keep it at that, anatomically speaking?”

I said that I would.

Again with the jabbing finger. The nail in need of trimming, a brown line at the distal edge. His grin was manic; an odd light danced in his eyes. “Don’t shit in my hat and tell me it’ll fit better.”

I confirmed that I would not.

We finished our cigarettes and thumbed the butts into the receptacle. As we walked back to the building, two of the young women from customer service passed us, fishing packs of cigarettes from their purses. Artemis turned around to look. “Oh man,” he said. “Oh man.”

I worried about Artemis. His conflicts with management had grown more frequent over the course of several years, and he worked himself up into a rage at the merest perceived insult. I suspected that actual slights were in fact very rare, or at the very least harmless, or meant in jest. I feared that one day he would step over some line, or simply provoke the wrong person. What would become of him if he were fired? He was nearing 60, and the skills he brought to bear at A.I.I. did not translate well in the larger corporate world; moreover, the confidentiality agreement that he—that all of us—had signed was stringent and strict and carried outsized professional and personal penalties for those who might violate it.

However, the man did wield incredible intellectual prowess; that I knew just from conversations over lunch and smoke breaks. When he was not preoccupied with cabals and conspiracies, he spoke at length about films from countries I’d never heard of, classical music, the writings of the great philosophers. Of late he’d become obsessed with the works of long-dead mystics and occultists, Crowley and Blavatsky and Geist and the like, and he spoke about them with almost childlike enthusiasm.

Man could, he insisted, and here I paraphrase to the point of possibly profound distortion—affect with his mind the world around him, not only plant life and weather systems, but sentient creatures. The more advanced man, the more studied man might even be able to affect the minds of other men—something far beyond the hypnosis propagated by hucksters and hacks. Maybe, he said, even inanimate objects. It was nothing as prosaic as telekinesis. It involved uttered sounds and elixirs and energies released into the “mindscape of the psychic environment”…man could, if he had the access to certain secret knowledge, imbue the very cells of things and beings around him with his will. Sometimes he would pull out a pen and draw formulae—three-dimensional equations of dizzying complexity, or else utter nonsense—on a restaurant napkin. I confess that most of what he said lay well beyond my capacity to understand it, and I would go to bed those nights with my neck aching from an abundance of polite nodding. He either did not notice or generously chose to ignore the fact that I would contribute virtually nothing to these discussions.

In contrast to Artemis, who liked to talk back, to spar, sometimes even without any intent beyond entertaining himself, my custom for the eight or so hours that constituted each workday consisted largely of going unnoticed as much as possible. I did the work that was assigned to me, and if I asked a question, it was not to challenge nor contradict, but to request information that might inform my tasks, or allow me to perform them more efficiently. If asked to do an unpleasant task, I assented cheerfully, and as a result my work existence was free of difficulty and of dramatics. Those I experienced vicariously through Artemis. I admit to having found some perverse entertainment in his paranoid fantasies.

What I couldn’t understand, though, was his leering after the young girls in the office. They were unformed, not yet fully come into being. They were a sculptor’s unfinished thing. They held no interest for me. To be fair, though, my libido had long been on some kind of downslide. It worried me, but only academically. Practically, the lack of that intense, cumbersome drive improved life both at work and outside of the office.

Not long after the ceiling work had begun, a separate group of workmen in blue jumpsuits arrived in a long white van, carrying with them duffle bags the approximate length of caskets. Workmen hustled them in pairs. Each had two vinyl handles and some inscrutable design sewn in with thread the color of Giallo movie blood. The workmen stacked the bags in the glass-walled conference room adjacent to the main hall over the course of an hour. Once they were all in, the workmen drew the shades, darkening the hall and piquing the curiosity of the staff, who gathered in clusters in the cafeteria to exchange theories and express frustration at the company's culture of secrecy.

The next day I planned to phone in to the office to beg off work for the day. I had been experiencing a mental fatigue whose symptoms were a pointed disinterest in completing the tasks I’d scheduled for the day, along with a general aversion to communicating in any medium with colleagues and clients and press. But before I could make the call, an email alert c

ame through on my phone. In order to complete the construction, it read, the office would be closed Thursday, Friday, and Monday, and business would resume Tuesday morning.

Tuesday came too soon. I shuffled in that morning to discover that the workers had extended the tracks from the halls into the offices, laboratories, cubicles, kitchens, meeting rooms, and stairwells. Mercifully, they did not extend into the lavatories. In all of our inboxes was an email. Finally they would reveal the purpose of the construction. I opened it and read.

As part of AII’s efforts to restructure and to focus our energies more fully on our work, we have taken the step of eliminating many of our middle management positions. Supervisory roles will now be filled remotely from our central office in Leeds, Massachusetts. Twelve men selected by Wren Black himself will fill these roles on our three east coast campuses. The supervisors will be represented here by the Kuklalar. The invention of Cordvassant Machines, the Kuklalar are humanoid marionettes, equipped with cameras and microphones. They will be present for your day-to-day activities. At least one will be present at every meeting. They will be the eyes and ears of Annelid Industries International.

The Kuklalar are not equipped for audio and will remain mute. It is not their job to interact, nor to tutor nor teach. They will not speak. On Monday morning of each week, your supervisor, represented by a Kuklala, will prepare a list of tasks and goals for the week ahead. At the end of the day, your supervisor will prepare a one-page report summarizing and analyzing your activities, followed by a weekly summary report on Friday afternoon. We invite you to join us in the atrium at 11:00 a.m. for an official introduction to our new supervisory staff. We expect that you’ll welcome them and afford them every courtesy.

The Stay-Awake Men & Other Unstable Entities

The Stay-Awake Men & Other Unstable Entities