- Home

- Matthew M Bartlett

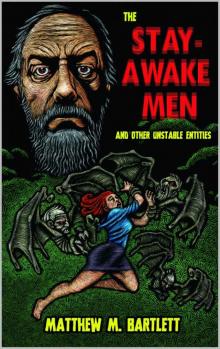

The Stay-Awake Men & Other Unstable Entities

The Stay-Awake Men & Other Unstable Entities Read online

The

Stay-Awake Men

& Other Unstable Entities

Matthew M. Bartlett

Copyright © 2016 Matthew M. Bartlett

All rights reserved.

First Kindle eBook edition.

This book is dedicated to Steven W. Kendrick.

I wish he could have been here for this.

BARTLETT AND YOU: AN UNSAFETY GUIDE

CARNOMANCER,

OR THE MEAT MANAGER’S PREROGATIVE

SPETTRINI

FOLLOWING YOU HOME

NO ABIDING PLACE ON EARTH

KUKLALAR

THE STAY-AWAKE MEN

THE BEGINNING OF THE WORLD

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

bartlett and you:

an unsafety guide

By Scott Nicolay

You may already know what I am going to say here, or at least you may think you do: Matthew Bartlett is one of those authors whose emergence redefines the genre. Barker, Ligotti, Barron, Llewellyn... Bartlett. And there I said it. Not that it will come as any surprise to you if you have read Gateways to Abomination and/or Creeping Waves...his importance is really a given at this point.

That’s really only a starting point though, isn’t it? It may well be the reason why you are here in the first place. You may have heard the rumors. You may think you know it already. You may even think you know what you are in for with this latest collection of his work.

But things are never what they seem chez Bartlett, are they? If you have played previously in his twisted playground (a setting he actually used in one of the most memorable stories from Gateways) you might anticipate a progression from creepy to disturbing to holy-shit-what-the-fuck, followed by a long hot shower and gargling with salt water to get the taste of pus and leeches out of your mouth (it won’t work, trust me). Critic s.j. bagley has described this payload delivery system of The Weird and its lingering effects as unsettlement...a deceptively understated term, especially in Bartlett’s case. He works like a decrepit Charon ferrying readers from the shores of the self to the unself, boatloads at a time, and for mere pennies. Each of his stories is a kind of haunted house that shunts you through multiple unexpected turns and shocks, rapidly deranging your narrative expectations until...it doesn’t really matter because the you who entered is no longer the reader who emerges.

Just so does my friend Matthew defy expectations afresh with each new tale. The reader cannot possibly know what you did going in because you never came out. Not that such knowledge would be much help anyway. Bartlett’s narratives follow no formula, not even their own. Every story is a unique labyrinth with its own rules, or rather, his labyrinth has no rules. Its corridors and catacombs are constantly shifting, ceaselessly changing, always Bartlett, never the same. There are many points of entry. No way out.

Here the reader, searching for some fixed reference, a place to attach one end of a long skein of colored yarn, may proclaim triumphantly: “But Bartlett’s stories all do have a common thread: WXXT, the sinister and mysterious radio station operated by an ancient and even more mysterious witch cult in Leeds, Massachusetts!”

So the reader may think...but that reader is neither you nor me. And the reader who is fortunate enough to have acquired a copy of this small volume is about to discover that our protean author has, like the slime mold, shifted into a new form and slithered on to new ground during the dark intervals of our eye blinks. You can’t step into the same Bartlett twice.

Oh, he is not without form, but no one has seen his true form. Though not all Weird writers are evolving, Bartlett, like rust, plasmodia, or The Weird itself, never rests. A certain type of reader might attempt to create a visual representation of the current amorphous state of The Weird, assigning a set of variable characteristics to each author and mapping our work along multiple axes in three or more dimensions. Such a display would likely reveal an overlapping array of lumpy blobs, many clustered closely together in unwholesome familiarity, others positioned at some greater remove from the crowd. Bartlettia would be one of the latter.

A similar approach to each individual author’s corpus might produce similar results, showing nuclear cores surrounded by more elastic pseudopodia extending in new directions. Variation within many populations would inevitably stand revealed as greater than that between the populations themselves. And within that dark star map, a graphic representation of the seven tale subset that comprises The Stay-Awake Men and Other Stories would indeed portray a single cluster and that cluster would still lie within the overall Bartlettosphere. These tale all give me that Bartlett Fink Feeling, true--but they belong to a new and distinct extrusion of that system. Of course it is no secret that Bartlett is going places. He always has been. Just not the places the reader expects.

So it is with The Stay-Awake Men and Other Stories (six other stories, to be exact): WXXT remains silent here. Leeds receives mention more than once--as does its major employer, Annelid Industries International--but though these are all distinctly Bartlett stories, none of them are “Leeds stories.” The titular tale is actually set at a radio station--but not WXXT. The différance is quite delicious, really. Amidst the familiar flavors in this batch of stew are tantalizing hints of Barker, Ligotti, Aickman, Samuels, and Klein, stronger than they have been before, but not strong enough to do more than add spice to the stock of an author who himself seems to grow in power with every paragraph. “Spettrini” (which previously appeared as a limited edition chapbook from Dunhams Manor Press) in particular invoked not only “The Glamour,” a long-standing personal favorite among Ligotti’s tales, but also Barker’s Imajica. Perhaps that was just me, but there is no way for me to tell now.

The Stay-Awake Men shows Bartlett not simply shifting his territory, but broadening it overall, becoming a little more literary perhaps, maybe a bit more strange or uncanny, as some prefer to style it in the Other England, the “Old” one. Part of that must come from the extent that the author has distopiated these tales, distancing them from one of the most distinctive locales in contemporary fiction. While the reader was distracted, Bartlett expanded, growing not only greater, but nearer. As his tales become less local, they become more universal. Was there a vacant house down the street from you? It may have a new occupant. Don’t worry if you can’t visit: it may come to you.

Oh look, here in your hands: it has already arrived. Oh well, time for me to leave. It was nice knowing you.

Bartlett’s house has many doors. Many gateways in. No way out. Don’t worry though. I think you will like it there.

carnomancer, or the meat manage r’s prerogative

LaFogg stared down through the two-way mirror at the new ginger-haired cashier as she bent to retrieve a coupon that had fallen from the dispenser. She was far too young for him to be ogling, he thought, but damned if she didn’t strongly resemble a younger iteration of KaraLee, his former wife, down to the spray of freckles across the back of her slender neck. She was going to grow up tall, he thought. Rangy. Leggy.

He was on the ugly side of his fifties, a mere half-inch taller than very short, with a protruding belly and a bald spot that stayed resolutely pink no matter the season: not exactly the kind of man the cashier would ever look at with anything other than indifference or even, he allowed, mild disgust. A noise escaped his mouth as she bent further and he saw the eye-shaped patch of pale skin between her store-issued yellow polo and her black leggings.

One of the customers in her line, a stooped, elderly man in a flat cap and windbreaker, looked up toward the offices and LaFogg reflexively took a step back. He knew no one could see through the glass, but the old cre

ep appeared to be looking right at him. He sat back down at his desk, opened up the quarterly sales report, and pretended to stare at it. The speaker above his desk squelched, and an electronic code sounded: three blips in rapid succession, a pause, and a fourth. A disruption on the floor. He grabbed the armrests of his chair and hoisted himself up, padded down the stairs as the voice of Grant, the assistant manager, came over the loudspeaker, An associate to Department 9 for customer assistance please. Department 9. Customer assistance.

Department 9 was Meats, located at the back of the store, opposite the registers. LaFogg walked briskly down the cereal aisle, occasionally breaking into a shambling, arrhythmic travesty of a jog. The bottom of his yellow shirt came untucked, flapping like a flag. An angled shopping cart blocked his way, helmed by a short Spanish lady intently comparing the Cap’n Crunch ingredients with those of Admiral Crispy, the market’s version. LaFogg sucked in his gut, squeezed by. A crowd had begun to form at the end of the aisle. He pushed through them, and then stopped short.

Crouched in the meat case that stretched between the deli and the dairy case was a baldheaded man. He looked to be in his forties, was barefoot, built like a professional wrestler, clad in checkered pants and a white apron stained pink with ghosts of bloodstains. His had monstrous arms carpeted with thick, wiry hair. LaFogg noticed a price sticker pinched into the man’s prodigious black mustache. With both hands he was lustily prying the cellophane from a huge hunk of bottom-round roast. Scattered across the tan and white tiled floor were torn shards of Styrofoam, sheets of pink-stained padding, and bunched remnants of cellophane, bubbled pink with blood. They looked to LaFogg like the sloughed-off skins of snakes. Among them sat the man’s shoes, placed evenly side by side, one black sock neatly folded in each.

LaFogg fumbled through a mental catalog of things to say, but came up empty. His mouth opened and closed. He held out his arms, and realized he hadn’t planned anything in particular for them to do. He let them fall back to his side and settled for arranging his face into an affronted expression. Two policemen pushed past him. “Sir,” shouted the taller of the two. “Climb down out of there and get down on the floor.”

The man grinned at them, revealing bright white, gleaming teeth, as though from a toothpaste commercial. His mustache, by contrast, was so black it appeared to have been dyed. “It’s in here somewhere,” he said. “It has to be in here somewhere.” With that, he turned his attention back to the roast. He began tearing it open with his hands, digging in his nails, pulling it apart. The policemen descended upon him, hooked their arms through his, and hauled him up out of the case. The roast fell to the floor with a moist thump. One cop forced the man to the ground and wrenched his arms behind his back. The other knelt on his legs and cuffed him. The man cried out, a howl of frustrated rage, and thrust out a hand toward the roast, muscles straining, perfect teeth clenched. Then he looked at LaFogg. And smiled.

Rekka, one of the deli men, blonde-haired, squinty eyed and slouchy, came over and stood at LaFogg’s side. Rekka surveyed the scene, looking from where the policemen were hoisting the man up to his feet, past the pink and red wreckage in the meat case, down to the tattered cellophane on the floor, then back, over the faces of the gathered crowd. He was grinning avidly. “Who is that?” LaFogg said.

“That,” Rekka said, “is Foxcroft. He is the Meat Manager.” He laughed. “Was the Meat Manager.”

“I’ve never seen him here,” LaFogg said.

“He’s been here, like, forever,” said Rekka.

It was mid-December. The first snow of the season had fallen the week before, and three consecutive 40-degree days melted most of it away. All that remained was brown-topped hillocks of pebble-pimpled snow gathered at the curbs like trash. The landscape was a hundred muddy shades of brown, fallen leaves, denuded trees, dirt-dusted blacktop, brown-bricked houses squatting like frogs in a polluted pond, all of it domed by a cadaver-grey sky. LaFogg piloted his Caprice through the maze of parking lots and dumpsters and boulder-strewn landscaping, then onto Haines Boulevard, a long, ruler-straight street of three-story apartment houses where dead trees moped along the curb and intermittent fences of varying poor quality bracketed front yards overgrown or barren. LaFogg could tell which was his by the tree in front, the one doubled over as though in unbearable pain.

LaFogg’s eave-angled bedroom was lit blue by the moonlight outside: his small bed, its sheets twisted, the nightstand beside it, the dresser at its foot crowned by a dusty-screened 14-inch television. It was 7 p.m., early, and he wasn’t due back at the market until 11 the next day. Nevertheless, he undressed to his V-neck and his Fruit of the Looms, untied the knot of covers, and reclined on the bed, back to the wall. He groped for the remote and found it under the arch of his knee.

He started flipping rapidly through the channels—how do you even register what you’re seeing? KaraLee used to ask—when somewhere in there a flash of female flesh caught his eye. He flipped back through the channels until he found it: a shapely brunette with white angelic wings, standing before a red chaise lounge, black curtains undulating in slow-motion behind her. She wore a sheer white negligee, short, hemmed with lace. The broad sweep of the wings spreading behind her, framing her figure, set LaFogg’s imagination into motion: how the contours of her body would feel against his back as they soared over the city, her talons gripping his undershirt. She ran her hand along the curve of her hip, then down the length of her leg, crouching slightly, staring at the camera. Her lips were red, full, wet. A toll-free number appeared at the bottom of the screen. Call me, the woman said. I’m waiting. I’m so lonely here. Everyone has gone. It is gone. Do you have it? It has to be in here somewhere.

She turned and strode over to the chaise lounge, knelt on it, and began clawing at its seam, her rump up in the air, a high-heeled shoe dangling from her foot. That foot was filthy: there was mud smeared across her heel and caked between her toes like plaque. The sounds of the tearing, of rending, were terribly loud. He thumbed the volume down a few notches. The camera swam in and out of focus, and he saw that the chaise lounge was composed of large chunks of raw meat, veined and lined with white, glistening fat. The woman, possessed of a brutish strength, was splitting connective tissue, shredding the meat to bloody strips. The screen blurred to pixels, and came back into focus to reveal the woman’s appleskin-red lips spanning the little Sony. LaFogg could see the pores, the pink, stratified skin, the fine hairs of her face above the cupid’s bow. Call me, she whispered. Call me now.

The phone number seemed to ripple as the curtains continued to flutter in the background. LaFogg’s eyelids twitched, he let out a honk of a snore, and then he was in the room with the chaise lounge. The woman was gone. The curtains, still fluttering, parted to reveal the door that led to the butcher shop in the market. From somewhere beyond came a buzzing, as of insects in a state of agitation. LaFogg pushed his way through, felt his way through the familiar darkened corridor, lined with pallets. Ahead he saw a light rendered funereally grey by opaque plastic flaps. He divided them with his hands and pushed his way through into the workroom, held up his hand against the now harsh light.

The walls were white, dimpled in a cinquefoil pattern, damp from a new washing. Fatigue mats lined the floors in front of the work surfaces. At the far end of the room in a white smock and apron stood Foxcroft, his features obscured by a cap and a surgical mask. He was running a whirring blade down a column of grey meat, sheets of it falling at his feet. He turned, pulled down his mask, and silenced the electric knife. It has to be in here somewhere, he said, and his voice echoed around the room, each iteration slower and deeper than the last, until it was just a sepulchral drone. He turned and walked through a doorway to his right. LaFogg followed. In the next room, hanging from a metal rack by a hook through her feet, was the woman from the sex line commercial. She was flayed to the muscle, her skin piled off to the side like discarded clothing. Her wings hung dampened, limp, and stained red. The last of her blood was drip

ping from her body into an overflowing metal tray. Blood pooled in the center of the room, slowly spiraling down into a floor-spanning line of feather-clogged drains. Foxcroft drew from his smock a large chef’s knife and began hacking at the base of one of the wings. It has to be in here somewhere, he screamed, as blood sprayed in powerful, pulsing jets.

LaFogg awoke, kicked the covers away from him. The room was awash in light from the snowy television screen. He heard voices in the white noise, whispering to him. Go to the window, they said. Look and see. Look and see. He went to the window, put his hands on the cold glass, and looked out into the night. On the curb across the road was a man, tall, with a substantial belly like an overfilled pastry, his long overcoat unable to fully suppress its girth. He had a prodigious brown beard that the wind tossed about like a tree of dead leaves. Fists at his hips, he appeared to be striking a heroic pose, like a Viking at the helm of some great ship. As LaFogg watched, the man began to dance. It was a mournful dance, slow and deliberate, with no discernible pattern. To the sibilant music of the night he swayed, reached up his hands, shimmied, ducked, and twirled. His grace belied his heft. He was positioned between two yellow circles of streetlights. His features were hidden in shadows. No cars passed. The man danced and danced. LaFogg felt a hollow and howling feeling of tremendous loss surge up from the pit of his gut and climb the length of his spine. He yanked down the ragged, browned shade and returned to bed.

He fell instantly to sleep.

Three weeks later LaFogg sat in the break room, sliding the tines of his fork around the edges of a black plastic tray, prying up browned remnants of a Stouffer’s Macaroni & Cheese. The holidays were over and the workload had eased. Most of the staff had bounced back, gossiping with perverse enthusiasm, complaining about customers, smoking outside in chattering clusters, but he seemed to be stuck in a spiral of exhaustion, a despair whose source was a mystery to him. If someone came into the office where he was, he jumped as though a gunshot had gone off. When he woke in the mornings, he wished nothing more than to be unconscious again. He scraped off some burnt brown cheese and pushed it between his back teeth. The door behind him opened and Rekka came around and dropped into a chair across from him as though having fallen from a great height. “So!” he said. “Remember Foxcroft?”

The Stay-Awake Men & Other Unstable Entities

The Stay-Awake Men & Other Unstable Entities